The Only 2 Questions To Ask If You're Thinking Of Leaving Your Job

Hey everyone,

Oh, that grass, it’s always greener, isn’t it?

Whether they admit it or not I’m going to guess everyone thinks about changing careers. Eyeballing job postings, dreaming of working abroad from some South American hostel, wondering if it’s time to ask the big boss for a promotion into the open role sitting right above you.

I spent 10 years working at Walmart and over the course of those years I thought many times: “Should I do this, should I do that, should I apply for a role inside, should I apply for a role outside?”

When I left Walmart so I could focus on writing I called up my old boss Dave Cheesewright who gave me two helpful tests to make the decision.

Now, before I share the tests, I don’t want you to get me wrong. Sleepless nights, mental flip-flopping, moments of anxiety, that’s all part of it too. The goal is not to eliminate that vast array of emotions you’ll feel as you go through a career change. It’s a big decision! And it has huge consequences. Those emotions provide red, yellow and green lights along the path.

But the goal of these two tests is to eliminate any endless contemplation, to help rudder yourself, and just make sure you’re steering your life the right way.

So what are the two tests?

1. The Deathbed Test. You need to ask yourself: “When I’m looking back on my life, from my deathbed, which one of these options will I regret not doing the most?” Use that answer to helpfully guide you. In her book ‘The Top Five Regrets of the Dying,’ palliative care nurse Bronnie Ware shares that the No. 1 regret in life is “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

2. The Plan B Test. This is a simple question: “What is my Plan B?” This is the what if it fails test. You have to fully contemplate that failure. Plan for it, envision it, live through it. Could you go back to your former job or former company? Would you go get that degree you always wanted or move to Spain and take that painting class? Or would the bottom fall out of your finances completely? Your Plan B must be comfortable enough to prevent you from freezing you into risk-averse behavior after you make your move. Because if you’re picturing an empty bank account, you won’t take the chances you need to take to be successful in your next act.

For me I was thinking about whether I wanted to leave a big company to work as an author. My Deathbed Test told me “You better do this! You’ll regret it if you don’t!” and My Plan B Test told me “Well, it won’t be pretty, but if this whole thing falls to ruins, I guess I’ll polish the resume, knock on doors, and try and find another job.”

It didn’t sound so bad when I put it that way.

I hope these two tests help you along your path.

Good luck,

Neil

There's one more principle I like to apply in these situations...the "HELL YES!"

Already where you want to be but still having a hard time getting stuff done? Here are the 10 things you can do each morning to help you make the most of your day.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays, or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

The most famous gratitude letter of all time?

Hey everyone,

I went down deep into the rabbit hole to interview Maria Popova recently. She’s the wonder behind The Marginalian (formerly called Brainpickings) and one of her 3 most formative books is ‘Leaves of Grass,’ originally self-published in 1855 by total unknown 35-year-old newspaperman Walt Whitman.

I bought a paperback of ‘Leaves of Grass’ and began flipping through it and the poems hit me—wow. They were rubber mallets to the forehead! Whitman tackles self-love, self-awareness, sensuality, and homoeroticism, among many other topics, in ways that were unheard of 169 years ago. No wonder the collection of poems, endlessly revised and re-edited until his death 37 years later, is often considered *the* classic of American poetry.

As I was researching the book I was somewhat shocked to discover that Walt Whitman is considered the inventor of the ‘book blurb’—you know, those glowing reviews slapped on every book telling you how good it is? Nobody had done that till Walt wrote to Total Intellectual Stud Ralph Waldo Emerson saying his work had inspired ‘Leaves of Grass’ and Emerson wrote him a glowing letter back—perhaps the greatest gratitude letter of all time!—which Whitman shrewdly excerpted onto the spine of the second edition, like this:

I Greet You

at the Beginning of A

Great Career

R.W. Emerson

Not bad! Maria told me that in her inexhaustible research on Whitman she discovered Emerson was never asked for permission and was actually quite pissed about this! But they made up years later.

Still, that original letter, from Emerson to Whitman, is a thing of beauty, and it is credited with spiking the popularity of ‘Leaves of Grass’ to its place of preeminence today.

Here’s the letter in full with three somewhat-illegible pics below compliments of the Library of Congress followed by the text in full:

Dear Sir,

I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of "Leaves of Grass." I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit & wisdom that America has yet contributed. I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us happy. It meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile & stingy Nature, as if too much handiwork or too much lymph in the temperament were making our western wits fat & mean. I give you joy of your free & brave thought. I have great joy in it. I find incomparable things said incomparably well, as they must be. I find the courage of treatment, which so delights us, & which large perception only can inspire. I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start. I rubbed my eyes a little to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty. It had the best merits, namely, of fortifying & encouraging.

I did not know until I, last night, saw the book advertised in a newspaper, that I could trust the name as real & available for a post-office. I wish to see my benefactor, & have felt much like striking my tasks, & visiting New York to pay you my respects.

R.W. Emerson

Letter to Walter Whitman July 21, 1855

Nice, isn't it! What's the takeaway?

Just that words have power and letters of gratitude are so rare these days. If you send one, you never know, you just might change someone's life.

So in a way this letter is a little reminder to tell somebody who's doing a great job that they're doing a great job. Doesn't cost a lot! But perhaps changes a great deal.

Have a wonderful week everyone,

Neil

Did that whet your appetite for some poetry? Here is a silly, if perennially prescient, favorite from Roald Dahl.

And a beauty that echos Whitman from J. Drew Lanham.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays, or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

How To Have More (And Better!) Vacation

I researched broken vacation policies.

The solution is not what you think.

Hey everyone,

I thought as we get close to 'summer vacation' time I'd share an article I wrote with Shashank Nigam for Harvard Business Review about the idea of 'forced' vacation time. Has the idea caught on? No! Not at all! And yet: I keep thinking it has legs. It certainly worked at this small business. Take a read and I'd love to hear what your organization does to make vacation really work...

Neil

What One Company Learned from Forcing Employees to Use Their Vacation Time

Written by Neil Pasricha & Shashank Nigam

Have you ever felt burned out at work after a vacation? I’m not talking about being exhausted from fighting with your family at Walt Disney World all week. I’m talking about how you knew, the whole time walking around Epcot, that a world of work was waiting for you upon your return.

Our vacation systems are completely broken. They don’t work.

The classic corporate vacation system goes something like this: You get a set number of vacation days a year (often only two to three weeks), you fill out some 1996-era form to apply for time off, you get your boss’s signature, and then you file it with a team assistant or log it in some terrible database. It’s an administrative headache. Then most people have to frantically cram extra work into the week(s) before they leave for vacation in order to actually extract themselves from the office. By the time we finally turn on our out-of-office messages, we’re beyond stressed, and we know that we’ll have an even bigger pile of work waiting for us when we return. What a nightmare.

For most of us, it’s hard to actually use vacation time to recharge. So it’s no wonder that absenteeism remains a massive problem for most companies, with payrolls dotted with sick leaves, disability leaves, and stress leaves. In the UK, the Department for Work and Pensions says that absenteeism costs the country’s economy more than £100 billion per year. A white paper published by the Workforce Institute and produced by Circadian, a workforce solutions company, calls absenteeism a bottom-line killer that costs employers $3,600 per hourly employee and $2,650 per salaried employee per year. It doesn’t help that, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the United States is the only country out of 21 wealthy countries that doesn’t require employers to offer paid vacation time. (Check out this world map on Wikipedia to see where your country stacks up.)

Would it help if we got more paid vacation? Not necessarily. According to a study from the U.S. Travel Association and GfK, a market research firm, just over 40% of Americans plan not to use all their paid time off anyway.

So what’s the progressive approach? Is it the Adobe, Netflix, or Twitter policies that say take as much vacation as you want, whenever you want it? Open-ended, unlimited vacation sounds great on paper, doesn’t it? Very progressive, right? No, that approach is broken too.

What happens in practice with unlimited vacation time? Warrior mentality. Peer pressure. Social signals that say you’re a slacker if you’re not in the office. Mathias Meyer, the CEO of German tech company Travis CI, wrote a blog post about his company abandoning its unlimited vacation policy: “When people are uncertain about how many days it’s okay to take off, you’ll see curious things happen. People will hesitate to take a vacation as they don’t want to seem like that person who’s taking the most vacation days. It’s a race to the bottom instead of a race towards a well rested and happy team.”

The point is that in unlimited vacation time systems, you probably won’t actually take a few weeks to travel through South America after your wedding, because there’s too much social pressure against going away for so long. Work objectives, goals, and deadlines are demanding. You look at your peers and see that nobody is backpacking through China this summer, so you don’t go either. You don’t want to let your team down, so your dream of visiting Machu Picchu sits on the shelf forever.

What’s the solution?

Recurring, scheduled mandatory vacation.

Yes, that’s right — an entirely new approach to managing vacation. And one that preliminary research shows works much more effectively.

Designer Stefan Sagmeister said in his TED talk, “The Power of Time Off,” that every seven years he takes one year off. “In that year,” he said, “we are not available for any of our clients. We are totally closed. And as you can imagine, it is a lovely and very energetic time.” He does warn that the sabbaticals take a lot of planning, and that you get the most benefit from them after you’ve worked for a significant amount of time.

Why does he do this? He says, “Right now we spend about the first 25 years of our lives learning, then there are another 40 years that are really reserved for working. And then tacked on at the end of it are about 15 years for retirement. And I thought it might be helpful to basically cut off five of those retirement years and intersperse them in between those working years.” As he says, that one year is the source of his creativity, inspiration, and ideas for the next seven years.

I recently collaborated with Shashank Nigam, the CEO of SimpliFlying, a global aviation strategy firm of about 10 people, to ask a simple question: “What if we force people to take a scheduled week off every seven weeks?”

The idea was that this would be a microcosm of the Sagmeister principle of one week off every seven weeks. And it was entirely mandatory. In fact, we designed it so that if you contacted the office while you were on vacation — whether through email, WhatsApp, Slack, or anything else — you didn’t get paid for that vacation week. We tried to build in a financial punishment for working when you aren’t supposed to be working, in order to establish a norm about disconnecting from the office.

The system is designed so that you don’t get a say in when you go. Some may say that’s a downside, but for this experiment, we believed that putting a structure in place would be a significant benefit. The team and clients would know well ahead of time when someone would be taking a week off. And the point is you actually go. And everybody goes. So there are no questions, paperwork, or guilt involved with not being at the office.

After this experiment was in place for 12 weeks, we had managers rate employee productivity, creativity, and happiness levels before and after the mandatory time off. (We used a five-point Likert scale, using simple statements such as “Ravi is demonstrating creativity in his work,” with the options ranging from one, Strongly Disagree, to five, Strongly Agree.) And what did we find out?

Creativity went up 33%, happiness levels rose 25%, and productivity increased 13%. It’s a small sample, sure, but there’s a meaningful story here. When we dive deeper on creativity, the average employee score was 3.0 before time off and 4.0 after time off. For happiness, the average employee score was 3.2 before time off and 4.0 afterward. And for productivity, the average employee score was 3.2 before and rose to 3.6.

This complements the feedback we got from employees who, upon their return, wrote blog posts about their experiences with the process and what they did with their time. Many talked about how people finally found time to cross things off of their bucket lists — finally holding an art exhibition, learning a new language, or traveling somewhere they’d never been before.

Now, this is a small company, and we haven’t tested the results in a large organization. But the question is: Could something this simple work in your workplace?

There were two points of constructive feedback that came back from the test:

Frequency was too high. Employees found that once every seven weeks (while beautiful on paper) was just too frequent for a small company like SimpliFlying. Its competitive advantage is agility, and having staff take time off too often upset the work rhythm. Nigam proposed adjusting it to every 12 weeks. But with employee input, we redesigned it to once every eight weeks.

Staggering was important. Let’s say that two or three people work together on a project team. We found that it didn’t make sense for these people to take time off back-to-back. Batons get dropped if there are consecutive absences. We revised the arrangement so that no one can take a week off right after someone has just come back from one. The high-level design is important and needs to work for the business.

This is early research, but it confirms something we said at the beginning: Vacation systems are broken and aren’t actually doing what they’re advertised to do. If you show up drained after your vacation, that means you didn’t get the benefit of creating space.

Why is creating space so important?

Consider this quote from Tim Kreider, who wrote “The ‘Busy’ Trap” for the New York Times:

Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice; it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets. The space and quiet that idleness provides is a necessary condition for standing back from life and seeing it whole, for making unexpected connections and waiting for the wild summer lightning strikes of inspiration — it is, paradoxically, necessary to getting any work done.

Fix your vacation system. You’ll be doing better, more important work.

Contrary to popular discourse, we actually do like to work...

...But that doesn't mean you're in the right job to feel fulfilled—even if it has a great vacation policy!

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays, or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

The fundamental unit of urban life

Hey everyone,

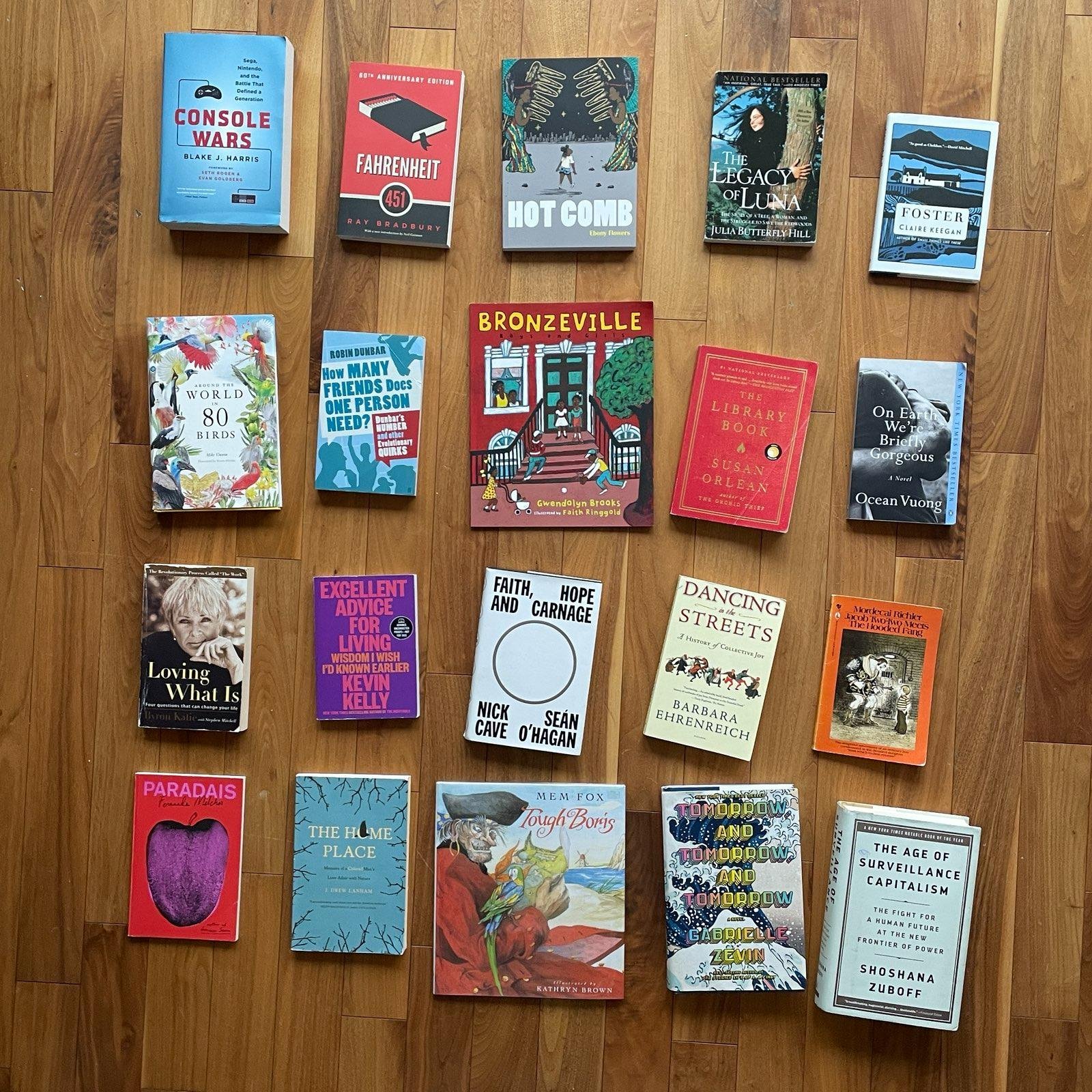

I've been a subscriber on Robin Sloan's email list for a while. He's the author of 'Moonbound,' 'Sourdough,' and 'Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore.' I noticed in his last email he had a nice little ode about the value of local restaurants—and local small business, in general.

As Robin writes:

It is physical establishments—storefronts and markets, cafes and restaurants—that makes cities worth inhabiting. Even the places you don't frequent provide tremendous value to you, because they draw other people out, populating the sidewalks. They generate urban life in its fundamental unit, which is: the bustle.

I love that! Jane Jacobs, author of 'The Death and Life of Great American Cities,' said, "By its nature, the metropolis provides what otherwise could be given only by traveling; namely, the strange." I love strange. I fear the WALL-E-like days with drone-delivered Amazon packages dropping over everybody's tall hedges and gated drives while Main Street is all boarded up.

The whole piece reminds me of a word Roger Martin taught us—or taught me, at least!—back in Chapter 68 of 3 Books which is "multi-homing." Simply remembering that, as consumers, we have the power to resist the "single home" desires of most companies—just use Uber for rides! just use Meta for social! just use Netflix for TV!—and spread our dollars around.

I think of this when I see neighborhood hardware stores go under while we all Amazon packs of nails to ourselves instead of walking down the street.

I'm trying to keep focusing on small business—buying local, supporting my neighbors—and this essay was a nice reminder. I hope you enjoy it. To check out more of Robin's work, including his new book 'Moonbound,' visit his website here or sign up for his email list here.

Have a great week everyone,

Neil

Public Service: Good To Eat

Written by Robin Sloan

I’m an ardent booster of my little neighborhood, roughly where Oakland, Berkeley, and Emeryville mash together, up against the railroad tracks, an old meatpacking district now residential (small single-family, sprawling condo) and industrial (the country’s tastiest jam, sophisticated cardboard box manufacturing machines) and intellectual (mostly biotech, including a mycelium leather lab).

Berkeley Bowl West, arguably the best grocery store in the country, sits along a bucolic greenway.

There are also restaurants, of course, and one in particular has transformed and enlivened the entire neighborhood. Called Good to Eat, it is the brick-and-mortar realization of a pop-up that for many years offered Taiwanese dumplings at a local brewery. The restaurant is approaching its second anniversary; it has become my favorite in the entire Bay Area.

Good to Eat is the vision of Tony Tung and Angie Lin. Chef Tony is the kitchen mastermind, honoring and renewing classic Taiwanese cuisine. Angie is, among many other things, the restaurant’s voice on Instagram, a fountain of energy and invitation. (Her record, in Instagram Stories, of a recent research trip to Taiwan was basically a mini-documentary.)

A sign of great people is that they attract great people, and Good to Eat’s whole team sparkles. It feels most nights like there must be a camera crew perched just out of sight, filming a segment for some children’s TV show, intended to model “careful work” and “cheerful collaboration” for impressionable young minds.

And there is a surprise here. The casual, friendly service and reasonable (for the Bay Area) prices don’t quite prepare you for the food, which exhibits a level of precision and creativity that approaches fine dining. It’s delightful to realize: all those years with the pop-up, slinging dumplings, THIS is what Chef Tony wanted to do. She had a secret plan!

Just look at this menu.

(If I was ordering today, right now, I’d get the eggplant noodle, the golden kimchi — my favorite kimchi I’ve had anywhere — the bok choy, and, yes, the fu-ru fried chicken. But this would imply NOT getting the red-braised pork belly with daikon radish … hmm … )

All together, it is a perfect package: food, space, esprit de corps. Of course, it helps that Kathryn and I have known these folks since their pop-up days, and are always greeted warmly … but visit twice, and you’ll be greeted warmly, too.

Good to Eat offers the tangible argument: enthusiasm and care are not in short supply. They don’t need to be hoarded. They ought to burn bright, spill out onto the sidewalk.

Here’s something important to understand. It is, at this time, approximately impossible to open and operate a restaurant in the Bay Area. The exorbitant cost of every input yields eye-popping menu prices; those prices keep customers away; the whole commercial equation becomes tenuous. There has been a wave of closures, as longstanding favorites throw in the towel.

It’s not just restaurants. Every kind of physical establishment feels, presently, improbable. It’s so much easier to … do something else. Anything else! Yet, it is physical establishments — storefronts and markets, cafes and restaurants — that make cities (like the donut megalopolis of the Bay Area) worth inhabiting. Even the places you don’t frequent provide tremendous value to you, because they draw other people out, populating the sidewalks. They generate urban life in its fundamental unit, which is: the bustle.

In taking on this task — setting out their sandwich board (you know I love a sandwich board) and opening their doors to everyone — people like Tony and Angie provide a profound public service.

It shouldn’t be so difficult! And this is not just a post-pandemic thing. The Bay Area has, for decades, been a daunting place to open your doors. Many of America’s urban hubs share this overheated deformity. It’s breathtaking to visit a country like Japan and find the most tenuous businesses (with the scantest hours) puttering along happily … simply because the rent is so low.

The shortage of useful, flexible space imposes costs — opportunity costs, if you remember econ 101 — borne by all of us, not just the Tonys and Angies of the world. Maybe that’s fair payment for the other gifts these places provide … but I’m skeptical. We don’t know, will never know, what we’re missing, except that it’s a lot.

Anyway, this is all to say: these days, it’s a minor miracle when a great new restaurant opens and stays open, so if you’re in the Bay Area, you should make haste to 65th Street in Emeryville. The patio is lovely, but/and Kathryn and I always sit at the bar. Get the kimchi. Yeah … get the fried chicken, too.

P.S. Shoutout to Michael Werner who responded to this post by sharing a delightful Kurt Vonnegut story from a PBS interview with journalist David Brancaccio about telling his wife he's going out to buy an envelope:

Oh, she says, well, you're not a poor man. You know, why don't you go online and buy a hundred envelopes and put them in the closet?

And so I pretend not to hear her. And go out to get an envelope because I'm going to have a hell of a good time in the process of buying one envelope. I meet a lot of people. And, see some great looking babes. And a fire engine goes by. And I give them the thumbs up. And, and ask a woman what kind of dog that is. And, and I don't know. The moral of the story is, is we're here on Earth to fart around. And, of course, the computers will do us out of that. And, what the computer people don't realize, or they don't care, is we're dancing animals. You know, we love to move around. And, we're not supposed to dance at all anymore.

You know what else makes cities great? Bookstores! And you should spend more time visiting them.

But not every neighborhood has great access to books. Listen to my interview with Latanya and Jerry of Bronx Bound Books to learn how they’re using a bus to bring books to the Bronx.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays, or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

Want to beat the algorithm? Don't play the game

How often are you too busy?

Like the fizz is bubbling over the lip of your cup?

Me, honestly, more often than I’d like. I think of myself as a writer. You know: urban flâneuring between coffee shops where I drip out paragraphs of poignancy for my next book.

But, in reality: I got deadlines! At least once or twice a week I look at my to-do list and a little fireball of stress bubbles up inside. Podcasts need editing, posts need writing, slides need building, and, you know, sure: I have some good systems—Parkinson's Law! Untouchable Days! Productivity tips up the wazoo!—but the truth is there’s some bigger issue culturally and I find it helpful to stay aware of it.

A dozen years ago Tim Kreider called the problem the ‘busy’ trap, pointing out that people telling you how busy they are has "become the default response when you ask anyone how they’re doing."

As Tim writes:

Even children are busy now, scheduled down to the half-hour with classes and extracurricular activities. They come home at the end of the day as tired as grown-ups. I was a member of the latchkey generation and had three hours of totally unstructured, largely unsupervised time every afternoon, time I used to do everything from surfing the World Book Encyclopedia to making animated films to getting together with friends in the woods to chuck dirt clods directly into one another’s eyes, all of which provided me with important skills and insights that remain valuable to this day. Those free hours became the model for how I wanted to live the rest of my life.

And this was in 2012 before the Internet bullet train accelerated into the everything-blurry-out-the-window mode we're cruising at now.

Tim called this busyness out and said we’re feeling too anxious or guilty when we aren’t working. I know I was definitely busy in 2012—I had gone through a divorce and was living in a tiny downtown condo while working as chief of staff for Dave Cheesewright by day, writing 1000 Awesome Things every night, and stuffing in writing of three books and a couple page-a-day calendars while also giving talks every weekend. I felt beyond busy—more dead-man-walking, really, getting 3-4 hours of sleep a night, and coming to epitomize the definition of burnout.

Another person I have found helpful on my journey since then is Douglas Rushkoff. Back in 2012, in my high-burnout years, he was named by MIT Technology Review the 6th most influential thinker in the world (behind heavyweights like Daniel Kahneman and Steven Pinker) although I didn't personally find him until I read his 'Team Human' a few years later. That book sang to my soul and I put it in one of my Very Best Books lists.

I’ve since followed everything Douglas. I started listening to his biweekly Team Human podcast and he was kind enough to blow our minds on 3 Books where his distillation of 'Go, Dog! Go' by P. D. Eastman may be the best children’s book analysis I’ve heard. He then increased the publishing schedule of Team Human and he started up a new Substack newsletter. At age 63, after dozens of books and documentaries, while working full-time as a professor, it seemed he was accelerating into Peak Douglas!

But then he came back to his team human roots and on May 3, 2024 he published a wonderful piece called 'Breaking from the Pace of the Net' with the opening line "I can’t do this anymore."

He goes on to explain:

Oh, I’m happy to write and podcast and teach and talk. That’s me, and that’s all good. What I’m finding difficult, even counter-productive, is to try to keep doing this work at the pace of the Internet.

Podcasting is great fun, and if it were lucrative enough I could probably record and release one or two episodes a week without breaking too much of a sweat. That’s the pace encouraged by both the advertising algorithms and the patronage platforms. Advertisers can more easily bid for spots on a show with a predictable schedule on specified days. Likewise, paying subscribers have come to expect regular content from the podcasts they support. Or at least the platforms encourage a regular rhythm, and embed subtle cues for consistency.

Substack, while great for a lot of things, is even worse as far as its implied demand for near-daily output. If I really wanted to live off a Substack writing career, I would have to ramp up to at least three posts a week. That might work if I were a beat reporter covering sports, but - really - how many cogent ideas about media, society, technology and change can one person develop over the course of a week? More important, how many ideas can one person come up with that are truly worth other people’s time?

I relate deeply to this feeling. The thirsty more-ness the Internet demands! When I launched 3 Books in 2018 it zoomed up the Apple rankings and became one of the Top 100 shows in the world. My podcast friends started texting me "Release your show weekly! Daily! You’ll stay on top!" But I was committed to my lunar-based schedule—I knew I needed time to properly prepare and go deep on each chat—and, of course, the algorithms punished me for that. If others are posting weekly, or daily, or multiple-times-a-day, they will be rewarded for increasing eyeballs and ears on the platform and, unless you keep up, you’ll slowly slip away.

Back to Douglas:

… while I love being able to engage with readers and listeners and Discord members through many modes, I am coming to realize my sense of guilty obligation to all the people on all these platforms is actually misplaced. The platforms themselves are configured to tug on those triggers of responsibility, the same way Snapchat uses the “streak” feature to keep tween girls messaging each other every day. They’re not messaging out of social obligation, but to keep the platform’s metric rising. It’s early training for the way their eventual economic precarity will keep them checking for how much money a Medium post earned, or how many new subscribers were generated by a Substack post.

Most ironically, perhaps, the more content we churn out for all of these platforms, the less valuable all of our content becomes. There’s simply too much stuff. The problem isn’t information overload so much as “perspective abundance.” We may need to redefine “discipline” from the ability to write and publish something every day to the ability hold back. What if people started to produce content when they had actually something to say, rather than coming up with something to say in order to fill another slot?

I love that.

What if people started to produce content when they had actually something to say? It almost sounds so laughably arcane. This is the uncle of yours who posts on Instagram three times a year. But they’re of his birthday, the family reunion, and the time he was in Whistler and saw a Steller’s Jay. It’s the globe-trotting friend who sends a long email once a month—but they’re good, and juicy, and you feel like you’re there. Less is more!

Isn’t this exactly what Cal Newport’s been preaching in his new book 'Slow Productivity' where he encourages us to 1) do fewer things, 2) work at a natural pace, and 3) obsess over quality? Not easy when the Internet rewards doing more things, working at an unnatural pace, and obsessing over quantity.

Cal says the benefits that technology have accrued have also created the ability to stack more into our days than we can possibly handle. He points out that we’re overworked, overstressed, constantly dissatisfied, and trying to hit a bar that feels like it’s always moving up. One reason his book has struck a chord is because, in his words:

This lesson, that doing less can enable better results, defies our contemporary bias toward activity, based on the belief that doing more keeps our options open and generates more opportunities for reward.

Why? Because:

We've become so used to the idea that the only reward for getting better is moving toward higher income and increased responsibilities that we forget that the fruits of pursuing quality can also be harvested in the form of a more sustainable lifestyle.

A more sustainable lifestyle! That sounds good, doesn’t it? I think for me it’s worth checking in with myself to ensure I’m ‘working at a natural pace,’ which, thankfully, I seem to be getting better at than my grinding-till-4am-in-my-shoebox-condo days. And I need to keep relying on truth-tellers, like Tim, Douglas, and Cal here, to help me resonate with something I know deeply but, of course, often forget: life isn’t measured in outputs. It’s measured in love, in connection, in trust, in kindness, in passions, in memories. There are so many invisible but much-more-important guideposts when we look back on our lives from the end of it.

I like how Douglas ended his post with a thoughtful re-balancing act and a public commitment to realignment:

What I value most and, hopefully, offer is an alternative to the pacing and values of digital industrialism. That’s what I’m here for: to express and even model a human approach to living in a digital media environment. So I’m getting off the treadmill, recognizing this assembly line for what it is, and trusting that you will stay with me on this journey in recognition of the fact that less is more.

I’ll stay with you on your journey, Douglas. I like your style! And shall we revisit Tim Kreider, too? Near the end of 'The Busy Trap' he shares a note from a friend who left the rat race in the big city to live abroad:

The present hysteria is not a necessary or inevitable condition of life; it’s something we’ve chosen, if only by our acquiescence to it. Not long ago I Skyped with a friend who was driven out of the city by high rent and now has an artist’s residency in a small town in the south of France. She described herself as happy and relaxed for the first time in years. She still gets her work done, but it doesn’t consume her entire day and brain. She says it feels like college—she has a big circle of friends who all go out to the cafe together every night. She has a boyfriend again. (She once ruefully summarized dating in New York: “Everyone’s too busy and everyone thinks they can do better.”) What she had mistakenly assumed was her personality—driven, cranky, anxious and sad—turned out to be a deformative effect of her environment.

Let’s be wary of our environment. Our culture! How it’s forming, shaping, and styling itself around us, and how we may be bending, tilting, wilting against our natural preferences in ever-so-slight ways that we don’t always notice.

This post is a reminder, to myself, and maybe a few others, to keep checking in, valuing the big things, and steering ourselves towards space, time, and quality—while staying aware and resisting the pressures to do the opposite.

I’ll close with a short poem called 'Leisure' that I keep coming back to. It was written 113 years ago by Welsh poet W. H. Davies and it’s ever-so-simple but carries a reminder I like to tuck in my pocket whenever I find myself wondering whether or not to hit the gas.

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.No time to stand beneath the boughs

And stare as long as sheep or cows.No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass.No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night.No time to turn at Beauty's glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance.No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began.A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

I hope you find some time to stand and stare today.

—Neil

Want some inspiration to stop and stare? Listen to my 3 Books conversation on breaking boundaries to become better birdwatchers with J. Drew Lanham.

Can't put down your phone long enough to find a bird? Or feel like you have to turn that bird into content for the social media hype train? Here are 6 ways to reduce cell phone addiction.

Get my biweekly Neil.blog newsletter direct to your inbox:

A few pearls of wisdom from John Steinbeck ...

Hey everyone,

I am reading a most wonderful and wonderfully unusual book right now called 'The Log from the Sea of Cortez' by John Steinbeck. Pulitzer Prize-winning author of 'East of Eden,' 'Of Mice and Men,' and 'The Grapes of Wrath.' Did you know in 1940, after controversy erupted around 'The Grapes of Wrath' (“Communist! Labor-sympathizer! Socialist!”), Johnny decided to say eff y’all and ship out. Literally. He and his pal Ed hailed a sardine boat called the Western Flyer and went on a slightly bizarre, world-connecting, animal-collecting, pattern-seeing 4000 mile voyage around the Baja peninsula, into the Gulf of California aka The Sea of Cortez. You know that big long pinky finger of land hanging down the left side of Mexico? That! They sailed down and around that. Yes, I am embarrassed to say I didn’t know what it was called. But that's why we read! The book is arranged in a series of vivid diary entries through March and April 1940.

And it starts with little detailed observations like this on page 25:

A squadron of pelicans crossed our bow, flying low to the waves and acting like a train of pelicans tied together, activated by one nervous system. For they flapped their powerful wings in unison, coasted in unison. It seemed that they tipped a wavetop with their wings now and then, and certainly they flew in the troughs of the waves to save themselves from the wind. They did not look around or change direction. Pelicans seem always to know exactly where they are going.

Little observations. Rolling observations. Bits of philosophical insight between the observation and catalog of all the brightly colored things they’re pulling out of the water. Then it gets deeper and deeper:

The military mind must limit its thinking to be able to perform its function at all. Thus, in talking with a naval officer who had won a target competition with big naval guns, we asked, ‘Have you thought what happens in a little street when one of your shells explodes, of the families torn to pieces, a thousand generations influenced when you signal Fire?’ ‘Of course not,’ he said. ‘Those shells travel so far that you couldn’t possibly see where they land.’ And he was quite correct. If he could really see where they land and what they do, if he could really feel the power in his dropped hand and the waves radiating out from his gun, he would not be able to perform his function. He himself would be the weak point of his gun. But by not seeing, by insisting that it be a problem of ballistics and trajectory, he is a good gunnery officer. And he is too humble to take the responsibility for thinking. The whole structure of his world would be endangered if he permitted himself to think. The pieces must stick within their pattern or the whole thing collapses and the design is gone.

Damn! There’s a reason Maria Popova of the phenomenal The Marginalian says she considers this slender book of non-fiction Steinbeck's finest work.

This quote on Page 72 blew me away:

It was said earlier that hope is a diagnostic human trait, and this simple cortex symptom seems to be a primate factor in our inspection of our universe. For hope implies a change from present bad condition to a future better one. The slave hopes for freedom, the weary man for rest, the hungry for food. And the feeders of hope, economic and religious, have from these simple strivings of dissatisfaction managed to create a world picture which is very hard to escape. Man grows toward perfection; animals grow toward man; bad grows toward good; and down toward up, until our little mechanism, hope, achieve in ourselves probably to cushion the shock of thought, manages to warp our whole world. Probably when our species developed the trick of memory and with it the counterbalancing projection called ‘the future,’ this shock-absorber, hope, had to be included in the series, else the species would have destroyed itself in despair. For if ever any man were deeply and unconsciously sure that his future would be no better than his past, he might deeply wish to cease to live. And out of this therapeutic poultice we build our iron teleologies and twist the tide pools and the stars in to the pattern. To most men the most hateful statement possible is ‘A thing is because it is.’ Even those who have managed to drop the leading-strings of a Sunday-school deity are still led by the unconscious teleology of their developed trick.

And this one a few pages later scared me:

It is a rule in paleontology that ornamentation and complication precede extinction. And our mutation, of which the assembly line, the collective farm, the mechanized army, and the mass production of food are evidences or even symptoms, might well correspond to the thickening armor of the great reptiles—a tendency that can end only in extinction…

How about this doozy speaking about the cycles of time:

It is difficult, when watching the little beasts, not to trace human parallels. The greatest danger to a speculative biologist is analogy. It is a pitfall to be avoided—the industry of the bee, the economics of the ant, the villainy of the snake, all in human terms have given us profound misconceptions of the animals. But parallels are amusing if they are not taken too seriously as regards the animal in questions, and are downright valuable as regards humans. The routine of changing domination is a case in point. One can think of the attached and dominant human who has captured the place, the property, and the security. He dominates his area. To protect it, he has police who know him and who are dependent on him for a living. He is protected by good clothing, good houses, and good food. He is protected even against illness. One would say that he is safe, that he would have many children, and that his seed would in a short time litter the world. But in his fight for dominance he has pushed out others of his species who were not so fit to dominate, and perhaps these have became wanderers, improperly clothed, ill fed, having no security and no fixed base. These should really perish, but the reverse seems true. The dominant human, in his security, grows soft and fearful. He spends a great part of his time in protecting himself. Far from reproducing rapidly, he has fewer children, and the ones he does have are ill protected inside themselves because so thoroughly protected without. The lean and hungry grow strong, and the strongest of them are selected out. Having nothing to lose and all to gain, these selected hungry and rapacious ones develop attack rather than defense techniques, and become strong in them, so that one day the dominant man is eliminated and the strong and hungry wanderer takes his place.

These are just a few gems from 'The Log of the Sea of Cortez' by John Steinbeck. I'll publish a book review in my book club on Saturday and you can sign up here to get it:

A powerful 2-minute midday happiness intervention...

Want the secret to happiness?

Having friends.

That's it.

That's the big thing.

That's the biggest thing of all, really.

Robert Waldinger, Director of the 1938 Harvard Adult Development Study, the longest study ever on happiness, says: "... it’s not career achievement, money, exercise, or a healthy diet. The most consistent finding we’ve learned through 85 years of study is: Positive relationships keep us happier, healthier, and help us live longer. Period."

Sonja Lyubomirsky, University of California Professor and author of 'The How Of Happiness,' says: "Perhaps most critical to improving and maintaining happiness is the ability to connect with other people and to create meaningful connecting moments and even chemistry..."

Daniel Gilbert, Harvard Professor and author of 'Stumbling on Happiness,' says: “We are happy when we have family, we are happy when we have friends and almost all the other things we think make us happy are actually just ways of getting more family and friends.”

And yet: we are reporting fewer friends and fewer best friends than ever before.

Friendship is the number one driver to happiness! But we have less of it in our lives than we used to. Why? Online too much? Not connecting IRL? Upwardly mobility and geographically separating?

I sat down with Vivek Murthy a couple years ago — between Surgeon General stints — and he talked about our emerging epidemic of loneliness. Loneliness is a huge deal! It's worse for our health than smoking 15 cigarettes a day. In 2023 Vivek Murthy put out a Surgeon General's warning about the epidemic of loneliness and isolation.

So what's an easy 2-minute happiness intervention we can all do in the middle of our days?

Phone A Friend.

That's it.

Phone A Friend.

Just pick up the phone and phone a friend. What if they don't answer? Doesn't matter. A 2-minute voicemail or voicenote over text works just fine.

And who do you call?

Anybody from your 150!

Oxford Emeritus Professor Robin Dunbar, famous for coining Dunbar's Number, shared that we have a certain cognitive limit on friendship. Our brains support about 150 total friends, period, which he defines as "the sort of people you would like to spend time with if you have the chance, and would be willing to make the effort to do so." Friendship is two-way. We may be replacing a lot of previously two-way time with newer one-way digital relationships but we are happier when we feel more connected.

And 150 might feel familiar! It is also the average size of a wedding, the average number of people who see your Christmas card, and the average size of human villages for thousands of years.

So I'm suggesting your phone somebody in your 150. Ask yourself: Who would come to my wedding if I got married today? Who do I have, or would I have, on my holiday card mailing list?

Now what do you say?

I suggest three things:

State - State the value of the relationship. Tell them you mean something to them! "I was thinking about that time back in college....", "I loved seeing you over the holidays... ", "I just saw our mutual friend..."

Share - Share something going on with you. Something you're thinking about, wrestling with, struggling with. Vulnerability breeds connection! Share something going on in your life. We all have things we feel on top of and things we feel lost in. Share one of each!

Seek - Seek something. Ask a question! Give them something to respond to — a reason to reply with a note of their own. You could go small! "What are you up to this weekend? You could go big! "How do you think about developing your relationship with your in-laws?"

The truth is over the course of our lives we will all spend more and more time alone:

We have the Surgeon General telling us we have an epidemic of loneliness. Yet we know the number one driver of long-term happiness is friendship.

So what's the 2-minute intervention for a happier day?

It's simple.

Phone A Friend.

Enjoyed this article? Get my biweekly Neil.blog newsletter direct to your inbox:

A few thoughts on cell phone pervasiveness

Hey everyone,

Culture changes fast.

I remember the first time I walked by one of those winding 50-person lines at an airport Starbucks at six in the morning and thought "When did this happen?" Now it seems normal. I had the same thought last week when I stepped into the bathroom at O'Hare and stood facing a wall of eight urinals, with eight urinators standing in front of them, and every single one of them was ... looking at their phone. At awkward, elbow-at-chin-in-front-of-brick-wall-type angles, but still, it triggered the same thought in me: "When did this happen?"

When everyone has an addiction sometimes it looks like nobody has an addiction.

And, sure, sure, I'm addicted, too. But maybe that's why I find it helpful to try and at least see my behavior from different angles to observe what's changing. I think that's the first step to being more intentional.

I love the August 19, 2008 MIT Technology Review article by Jonathan Franzen called "I Just Called To Say I Love You" which is about 'cell phones, sentimentality, and the decline of public space.' The article feels old, sure, but was written just over 5000 days ago. I like the questions Franzen reminds us of, like when he says that "Privacy, to me, is not about keeping my personal life hidden from other people. It's about sparing me from the intrusion of other people's personal lives" or, when he talks about the fast-disappearing interactions we have (had?) with cashiers and discusses a person whipping through the checkout lane's "moral obligation to acknowledge [the cashier] as a person."

I pasted the first 1587 words of Franzen's 5775 word article below. Does it remind you of a place that's completely gone ... or maybe something we're starting to increasingly value? I know, for me, I've been leaving my phone home more often. I walk to the store, I buy cottage cheese, I walk home, and suddenly the walk feels a little more like something. I see more birds, talk to more people, and zoom out of my worries. I have also been locking my phone in a K-Safe before bed which gives me 8 or 12 hours completely 'phone free' each day.

Like I said: When everyone has an addiction sometimes it looks like nobody has an addiction.

Enjoy this excerpt from Jonathan Franzen below and let me know if it spurs something for you.

Neil

An excerpt from "I Just Called To Say I Love You" by Jonathan Franzen

Published August 19, 2008 in the MIT Technology Review.

One of the great irritations of modern technology is that when some new development has made my life palpably worse and is continuing to find new and different ways to bedevil it, I’m still allowed to complain for only a year or two before the peddlers of coolness start telling me to get over it already Grampaw–this is just the way life is now.

I’m not opposed to technological developments. Digital voice mail and caller ID, which together destroyed the tyranny of the ringing telephone, seem to me two of the truly great inventions of the late 20th century. And how I love my BlackBerry, which lets me deal with lengthy, unwelcome e-mails in a few breathless telegraphic lines for which the recipient is nevertheless obliged to feel grateful, because I did it with my thumbs. And my noise-canceling headphones, on which I can blast frequency-shifted white noise (“pink noise”) that drowns out even the most determined woofing of a neighbor’s television set: I love them. And the whole wonderful world of DVD technology and high-definition screens, which have already spared me from so many sticky theater floors, so many rudely whispering cinema-goers, so many open-mouthed crunchers of popcorn: yes.

Privacy, to me, is not about keeping my personal life hidden from other people. It’s about sparing me from the intrusion of other people’s personal lives. And so, although my very favorite gadgets are actively privacy enhancing, I look kindly on pretty much any development that doesn’t force me to interact with it. If you choose to spend an hour every day tinkering with your Facebook profile, or if you don’t see any difference between reading Jane Austen on a Kindle and reading her on a printed page, or if you think Grand Theft Auto IV is the greatest Gesamtkunstwerk since Wagner, I’m very happy for you, as long as you keep it to yourself.

The developments I have a problem with are the insults that keep on insulting, the injuries of yesteryear that keep on giving pain. Airport TV, for example: it seems to be actively watched by about one traveler in ten (unless there’s football on) while creating an active nuisance for the other nine. Year after year; in airport after airport; a small but apparently permanent diminution in the quality of the average traveler’s life. Or, another example, the planned obsolescence of great software and its replacement by bad software. I’m still unable to accept that the best word-processing program ever written, WordPerfect 5.0 for DOS, won’t even run on any computer I can buy now. Oh, sure, in theory you can still run it in Windows’ little DOS-emulating window, but the tininess and graphical crudeness of that emulator are like a deliberate insult on Microsoft’s part to those of us who would prefer not to use a feature-heavy behemoth. WordPerfect 5.0 was hopelessly primitive for desktop publishing but unsurpassable for writers who wanted only to write. Elegant, bug-free, negligible in size, it was bludgeoned out of existence by the obese, intrusive, monopolistic, crash-prone Word. If I hadn’t been collecting old 386s and 486s in my office closet, I wouldn’t be able to use WordPerfect at all by now. And already I’m down to my last old 486. And yet people have the nerve to be annoyed with me if I won’t send them texts in a format intelligible to all-powerful Word. We live in a Word world now, Grampaw. Time to take your GOI pill.

But these are mere annoyances. The technological development that has done lasting harm of real social significance–the development that, despite the continuing harm it does, you risk ridicule if you publicly complain about today–is the cell phone.

Just 10 years ago, New York City (where I live) still abounded with collectively maintained public spaces in which citizens demonstrated respect for their community by not inflicting their banal bedroom lives on it. The world 10 years ago was not yet fully conquered by yak. It was still possible to see the use of Nokias as an ostentation or an affectation of the affluent. Or, more generously, as an affliction or a disability or a crutch. There was unfolding, after all, in New York in the late 1990s, a seamless citywide transition from nicotine culture to cellular culture. One day the lump in the shirt pocket was Marlboros, the next day it was Motorola. One day the vulnerably unaccompanied pretty girl was occupying her hands and mouth and attention with a cigarette, the next day she was occupying them with a very important conversation with a person who wasn’t you. One day a crowd gathered around the first kid on the playground with a pack of Kools, the next day around the first kid with a color screen. One day travelers were clicking lighters the second they were off an airplane, the next day they were speed-dialing. Pack-a-day habits became hundred-dollar monthly Verizon bills. Smoke pollution became sonic pollution. Although the irritant changed overnight, the suffering of a self-restrained majority at the hands of a compulsive minority, in restaurants and airports and other public spaces, remained eerily constant. Back in 1998, not long after I’d quit cigarettes, I would sit on the subway and watch other riders nervously folding and unfolding phones, or nibbling on the teatlike antennae that all the phones then had, or just quietly clutching their devices like a mother’s hand, and I would feel something close to sorry for them. It still seemed to me an open question how far the trend would go: whether New York truly wanted to become a city of phone addicts sleepwalking down the sidewalks in icky little clouds of private life, or whether the notion of a more restrained public self might somehow prevail.

Needless to say, there wasn’t any contest. The cell phone wasn’t one of those modern developments, like Ritalin or oversized umbrellas, for which significant pockets of civilian resistance hearteningly persist. Its triumph was swift and total. Its abuses were lamented and bitched about in essays and columns and letters to various editors, and then lamented and bitched about more trenchantly when the abuses seemed only to be getting worse, but that was the end of it. The complaints had been registered, some small token adjustments had been made (the “quiet car” on Amtrak trains; discreet little signs poignantly pleading for restraint in restaurants and gyms), and cellular technology was then free to continue doing its damage without fear of further criticism, because further criticism would be unfresh and uncool. Grampaw.

But just because the problem is familiar to us now doesn’t mean steam stops issuing from the ears of drivers trapped behind a guy chatting on his phone in a passing lane and staying perfectly abreast of a vehicle in the slow lane. And yet: everything in our commercial culture tells the chatty driver that he is in the right and tells everybody else that we are in the wrong–that we are failing to get with the attractively priced program of freedom and mobility and unlimited minutes. Commercial culture tells us that if we’re sore with the chatty driver it must be because we’re not having as good a time as he is. What is wrong with us, anyway? Why can’t we lighten up a little and take out our own phones, with our own Friends and Family plans, and start having a better time ourselves, right there in the passing lane?

Socially retarded people don’t suddenly start acting more adult when social critics are peer-pressured into silence. They only get ruder. One currently worsening national plague is the shopper who remains engrossed in a call throughout a transaction with a checkout clerk. The typical combination in my own neighborhood, in Manhattan, involves a young white woman, recently graduated from someplace expensive, and a local black or Hispanic woman of roughly the same age but fewer advantages. It is, of course, a liberal vanity to expect your checkout clerk to interact with you or to appreciate the scrupulousness of your determination to interact with her. Given the repetitive and low-paying nature of her job, she’s allowed to treat you with boredom or indifference; at worst, it’s unprofessional of her. But this does not relieve you of your own moral obligation to acknowledge her existence as a person. And while it’s true that some clerks don’t seem to mind being ignored, a notably large percentage do become visibly irritated or angered or saddened when a customer is unable to tear herself off her phone for even two seconds of direct interaction. Needless to say, the offender herself, like the chatty freeway driver, is blissfully unaware of pissing anybody off. In my experience, the longer the line behind her, the more likely it is she’ll pay for her $1.98 purchase with a credit card. And not the tap-and-go microchip kind of credit card, either, but the wait-for-the-printed-receipt-and-then-(only then)-with-zombiesh-clumsiness-begin-shifting-the-cell-phone-from-one-ear-to-the-other-and-awkwardly-pin-the-phone-with-ear-to-shoulder-while-signing-the-receipt-and-continuing-to-express-doubt-about-whether-she-really-feels-like-meeting-up-with-that-Morgan-Stanley-guy-Zachary-at-the-Etats-Unis-wine-bar-again-tonight kind of credit card.

There is, to be sure, one positive social consequence of these worsening misbehaviors. The abstract notion of civilized public spaces, as rare resources worth defending, may be all but dead, but there’s still consolation to be found in the momentary ad hoc microcommunities of fellow sufferers that bad behaviors create. To look out your car window and see the steam coming out of another driver’s ears, or to meet the eyes of a pissed-off checkout clerk and to shake your head along with her: it makes you feel a little less alone.

To read the full article from Jonathan Franzen on MIT Technology review, click here.

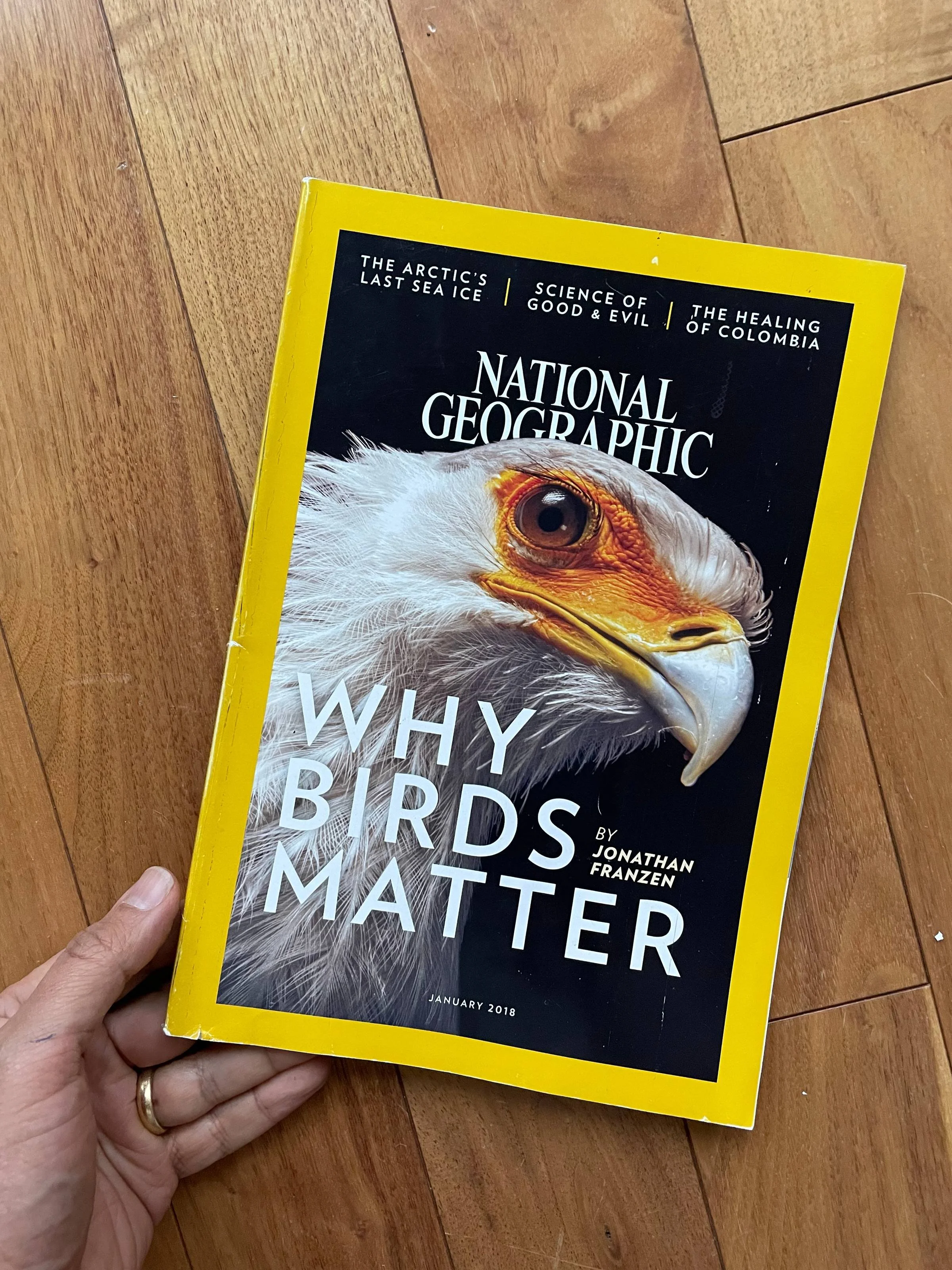

Why Birds Matter by Jonathan Franzen

Hey everyone,

I am often asked to explain my love of birds. “What?”, friends say, “you get up at the crack of down and slap on cargo points and a Tilley to futz around in the forest looking for sparrows?” I will say I know it sounds odd. But it’s become such a sacred commune with nature, with life, with the natural world. And, like my Rock Clock, it’s a wonderful zoom out, too.

One of the biggest things that got me into birding was the January, 2018 cover story “Why Birds Matter” by Jonathan Franzen. I have read it many times and it continues to deeply resonate. Franzen has a way of thinking around things that I find entrancing. My conversation with him on 3 Books only deepened my respect for him and how he approaches the world.

Hope you like it,

Neil

Why Birds Matter

By Jonathan Franzen | Read here on National Geographic

For most of my life, I didn’t pay attention to birds. Only in my 40s did I become a person whose heart lifts whenever he hears a grosbeak singing or a towhee calling and who hurries out to see a golden plover that’s been reported in the neighborhood, just because it’s a beautiful bird, with truly golden plumage, and has flown all the way from Alaska. When someone asks me why birds are so important to me, all I can do is sigh and shake my head, as if I’ve been asked to explain why I love my brothers. And yet the question is a fair one, worth considering in the centennial year of America’s Migratory Bird Treaty Act: Why do birds matter?

My answer might begin with the vast scale of the avian domain. If you could see every bird in the world, you’d see the whole world. Things with feathers can be found in every corner of every ocean and in land habitats so bleak that they’re habitats for nothing else. Gray gulls raise their chicks in Chile’s Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth.

Emperor penguins incubate their eggs in Antarctica in winter. Goshawks nest in the Berlin cemetery where Marlene Dietrich is buried, sparrows in Manhattan traffic lights, swifts in sea caves, vultures on Himalayan cliffs, chaffinches in Chernobyl. The only forms of life more widely distributed than birds are microscopic.

To survive in so many different habitats, the world’s 10,000 or so bird species have evolved into a spectacular diversity of forms. They range in size from the ostrich, which can reach nine feet in height and is widespread in Africa, to the aptly named bee hummingbird, found only in Cuba. Their bills can be massive (pelicans, toucans), tiny (weebills), or as long as the rest of their body (sword-billed hummingbirds). Some birds—the painted bunting in Texas, Gould’s sunbird in South Asia, the rainbow lorikeet in Australia—are gaudier than any flower. Others come in one of the nearly infinite shades of brown that tax the vocabulary of avian taxonomists: rufous, fulvous, ferruginous, bran-colored, foxy.

Birds are no less diverse behaviorally. Some are highly social, others anti. African queleas and flamingos gather in flocks of millions, and parakeets build whole parakeet cities out of sticks. Dippers walk alone and underwater, on the beds of mountain streams, and a wandering albatross may glide on its 10-foot wingspan 500 miles away from any other albatrosses. I’ve met friendly birds, like the New Zealand fantail that once followed me down a trail, and I’ve met mean ones, like the caracara in Chile that swooped down and tried to knock my head off when I stared at it too long. Roadrunners kill rattlesnakes for food by teaming up on them, one bird distracting the snake while another sneaks up behind it. Bee-eaters eat bees. Leaftossers toss leaves. Thick-billed murres can dive underwater to a depth of 700 feet, peregrine falcons downward through the air at 240 miles an hour. A wren-like rushbird can spend its entire life beside one half-acre pond, while a cerulean warbler may migrate to Peru and then find its way back to the tree in New Jersey where it nested the year before.

Birds aren’t furry and cuddly, but in many respects they’re more similar to us than other mammals are. They build intricate homes and raise families in them. They take long winter vacations in warm places. Cockatoos are shrewd thinkers, solving puzzles that would challenge a chimpanzee, and crows like to play. (On days so windy that more practical birds stay grounded, I’ve seen crows launching themselves off hillsides and doing aerial somersaults, just for the fun of it, and I keep returning to the YouTube video of a crow in Russia sledding down a snowy roof on a plastic lid, flying back up with the lid in its beak, and sledding down again.) And then there are the songs with which birds, like us, fill the world. Nightingales trill in the suburbs of Europe, thrushes in downtown Quito, hwameis in Chengdu. Chickadees have a complex language for communicating—not only to each other but to every bird in their neighborhood—about how safe or unsafe they feel from predators. Some lyrebirds in eastern Australia sing a tune their ancestors may have learned from a settler’s flute nearly a century ago. If you shoot too many pictures of a lyrebird, it will add the sound of your camera to its repertoire.

But birds also do the thing we all wish we could do but can’t, except in dreams: They fly. Eagles effortlessly ride thermals; hummingbirds pause in midair; quail burst into flight heart-stoppingly. Taken all together, the flight paths of birds bind the planet together like 100 billion filaments, tree to tree and continent to continent. There was never a time when the world seemed large to them. After breeding, a European swift will stay aloft for nearly a year, flying to sub-Saharan Africa and back, eating and molting and sleeping on the wing, without landing once. Young albatrosses spend as many as 10 years roving the open ocean before they first return to land to breed. A bar-tailed godwit has been tracked flying nonstop from Alaska to New Zealand, 7,264 miles in nine days, while a ruby-throated hummingbird may burn up a third of its tiny body weight to cross the Gulf of Mexico. The red knot, a small shorebird species, makes annual round-trips between Tierra del Fuego and the Canadian Arctic; one long-lived individual, named B95 for the tag on its leg, has flown more miles than separate the Earth and the moon.

There is, however, one critical ability that human beings have and birds do not: mastery of their environment. Birds can’t protect wetlands, can’t manage a fishery, can’t air-condition their nests. They have only the instincts and the physical abilities that evolution has bequeathed to them. These have served them well for a very long time, 150 million years longer than human beings have been around. But now human beings are changing the planet—its surface, its climate, its oceans—too quickly for birds to adapt to by evolving. Crows and gulls may thrive at our garbage dumps, blackbirds and cowbirds at our feedlots, robins and bulbuls in our city parks. But the future of most bird species depends on our commitment to preserving them. Are they valuable enough for us to make the effort?

Value, in the late Anthropocene, has come almost exclusively to mean economic value, utility to human beings. And certainly many wild birds are usefully edible. Some of them in turn eat noxious insects and rodents. Many others perform vital roles—pollinating plants, spreading seeds, serving as food for mammalian predators—in ecosystems whose continuing wildness has touristic or carbon-sequestering value. You may also hear it argued that bird populations function, like the proverbial coal-mine canary, as important indicators of ecological health. But do we really need the absence of birds to tell us when a marsh is severely polluted, a forest slashed and burned, or a fishery destroyed? The sad fact is that wild birds, in themselves, will never pull their weight in the human economy. They want to eat our blueberries.

What bird populations do usefully indicate is the health of our ethical values. One reason that wild birds matter—ought to matter—is that they are our last, best connection to a natural world that is otherwise receding. They’re the most vivid and widespread representatives of the Earth as it was before people arrived on it. They share descent with the largest animals ever to walk on land: The house finch outside your window is a tiny and beautifully adapted living dinosaur. A duck on your local pond looks and sounds very much like a duck 20 million years ago, in the Miocene epoch, when birds ruled the planet. In an ever more artificial world, where featherless drones fill the air and Angry Birds can be simulated on our phones, we may see no reasonable need to cherish and support the former rulers of the natural realm. But is economic calculation our highest standard? After Shakespeare’s King Lear steps down from the throne, he pleads with his elder two daughters to grant him some vestige of his former majesty. When the daughters reply that they don’t see the need for it, the old king bursts out: “O, reason not the need!” To consign birds to oblivion is to forget what we’re the children of.

A person who says, “It’s too bad about the birds, but human beings come first” is making one of two implicit claims. The person may mean that human beings are no better than any other animal—that our fundamentally selfish selves, which are motivated by selfish genes, will always do whatever it takes to replicate our genes and maximize our pleasure, the nonhuman world be damned. This is the view of cynical realists, to whom a concern for other species is merely an annoying form of sentimentality. It’s a view that can’t be disproved, and it’s available to anyone who doesn’t mind admitting that he or she is hopelessly selfish. But “human beings come first” may also have the opposite meaning: that our species is uniquely worthy of monopolizing the world’s resources because we are not like other animals, because we have consciousness and free will, the capacity to remember our pasts and shape our futures. This opposing view can be found among both religious believers and secular humanists, and it too is neither provably true nor provably false. But it does raise the question: If we’re incomparably more worthy than other animals, shouldn’t our ability to discern right from wrong, and to knowingly sacrifice some small fraction of our convenience for a larger good, make us more susceptible to the claims of nature, rather than less? Doesn’t a unique ability carry with it a unique responsibility?

A few years ago in a forest in northeast India, I heard and then began to feel, in my chest, a deep rhythmic whooshing. It sounded meteorological, but it was the wingbeats of a pair of great hornbills flying in to land in a fruiting tree. They had massive yellow bills and hefty white thighs; they looked like a cross between a toucan and a giant panda. As they clambered around in the tree, placidly eating fruit, I found myself crying out with the rarest of all emotions: pure joy. It had nothing to do with what I wanted or what I possessed. It was the sheer gorgeous fact of the great hornbill, which couldn’t have cared less about me.

The radical otherness of birds is integral to their beauty and their value. They are always among us but never of us. They’re the other world-dominating animals that evolution has produced, and their indifference to us ought to serve as a chastening reminder that we’re not the measure of all things. The stories we tell about the past and imagine for the future are mental constructions that birds can do without. Birds live squarely in the present. And at present, although our cats and our windows and our pesticides kill billions of them every year, and although some species, particularly on oceanic islands, have been lost forever, their world is still very much alive. In every corner of the globe, in nests as small as walnuts or as large as haystacks, chicks are pecking through their shells and into the light.

If you enjoyed this article, don’t miss Jonathan on Chapter 137 of 3 Books.

And if he didn’t manage to convince you, here are 8 reasons why it’s time to become a birdwatcher.

A few short thoughts on death...

Hey everyone,

Leslie’s grandmother Donna died recently. To quote the obituary she was a "dog whisperer, enthusiastic nature lover, savvy Scrabble player, intrepid traveler, Blue Jays fan, organizer of special occasions, chocolate chip cookie-maker, generous gift-giver, reader, and lover of maple syrup, chocolate, butter tarts, and all things sweet."

We had the burial — out in the cold, on a rainy day, over a hole in the ground in St. Catharines, Ontario. Her three living children all spoke and all the grandchildren (and grandchildren-in-law, like me) said a few words and threw a rose onto the urn holding her ashes.

I’ve been thinking a lot about death. I do that! It was the closing riff of my TED Talk and the basis of my TED Listen. More recently: Is death … avoidable? Or is it, to quote Saul Bellow, more like “the dark backing that a mirror needs if we are to see anything”?

First I’ll share a note I wrote to myself just after Donna died. In that sort of stunning silent phase. Then I’ll share two short poems read by her children (Leslie’s dad and aunt) at the burial. And, finally, let’s close with a quote on death from philosopher Bertrand Russell.

So, first up, my little note on how Donna died…

How Donna Died

Fast. That’s the first word that comes to mind. It happened quick. Like three months. Halloween she’s dressed as a ghost sitting beside me on the porch handing out candy. At 9pm, long after the streets had quieted, she said “I’m off to Jenny’s!” Leslie’s younger sister lived twenty minutes west — the exact opposite direction of her place. “Grandma,” Leslie said. “Don’t you want to head home? I’m sure Jenny would understand.” “Oh, don’t be silly! I’m a night owl!” We got a text the next morning with a picture of her squeezing our tiny niece dressed up as a pumpkin. She lost her license the next week. Hit the gas instead of the brakes in her parking garage. They said she had to get a health check. Health check said she had dementia. “Dementia?”, she scoffed. “Since when have I had dementia?” We never thought she had dementia. She forgot stuff. Who didn’t? Her boyfriend lost his license the next week. Suddenly we were talking carpools to drive grandma to her boyfriend’s place for the weekend. Then came the move. Her place finally sold and the new apartment was right downtown. We could walk from our house. “Scrabble every week,” we agreed. Week later that procedure finally came up that was scheduled months ago. For her bladder. But after the procedure she was in more pain — not less. Then they did another procedure to fix the first one. Then she was really cold for a few days. Then she couldn’t get out of bed. Then she got pale. Then Karen flew up. Then the cousins came. And then she died. Fast.

I miss you, Donna.

Next up, a poem read by Donna’s youngest daughter Karen (Leslie’s aunt) which Donna had cut out and taped to her fridge:

The Peace of Wild Things by Wendell Berry

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

It stuns me every time. Next up, a poem read by Donna’s son Mark (Leslie’s dad).

Immortality (Do Not Stand By My Grave and Weep) by Clare Harner

Do not stand

By my grave, and weep.

I am not there,

I do not sleep—

I am the thousand winds that blow

I am the diamond glints in snow

I am the sunlight on ripened grain,

I am the gentle, autumn rain.

As you awake with morning’s hush,

I am the swift, up-flinging rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight,

I am the day transcending night.

Do not stand

By my grave, and cry—

I am not there,

I did not die.

Not the kind of poem you can really read, or listen to, at someone's burial without crying. But I guess that's part of the point: a kind of philosophical adjustment, versus a physical adjustment, from the dead to the living. Somewhat related to both poems is this quote I found from Bertrand Russell in his essay “How To Grow Old.”

“The best way to overcome [the fear of death]—so at least it seems to me—is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The person who, in old age, can see life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he or she cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.”