May 2020.

Early pandemic.

Screechy zoom call in my kid’s bedroom.

My eyes gaze out the window.

I see a robin on a wire.

Wait.

Is that a robin?

The call ends and I run to the basement.

I pull open a bin in the storage room and find binoculars.

I run up and hold them up to my eyes.

I twiddle the dial and it suddenly pops—

I was blown away!

What was this bird?

Wait, what was that app Alec was telling me about last week after tennis?

The one where he clicked some buttons—

—and told us the little bird playing in the dirt outside the tennis courts was a ... House Finch?

Oh, right!

I remembered Alec's line.

“It’s the name of a wizard … and the name of a bird.”

Merlin!

I opened the App Store and typed in “merlin” and downloaded it.

I clicked some buttons—

And found out the bird out my window was a ... Rose-breasted Grosbeak!

I had never seen one before!

I looked out the window again and now there were two.

Maybe three?

Next week we ordered and set up a trampoline in our backyard.

The Rose-breasted Grosbeaks hung out on the wires above my kids jumping up and down for a few days.

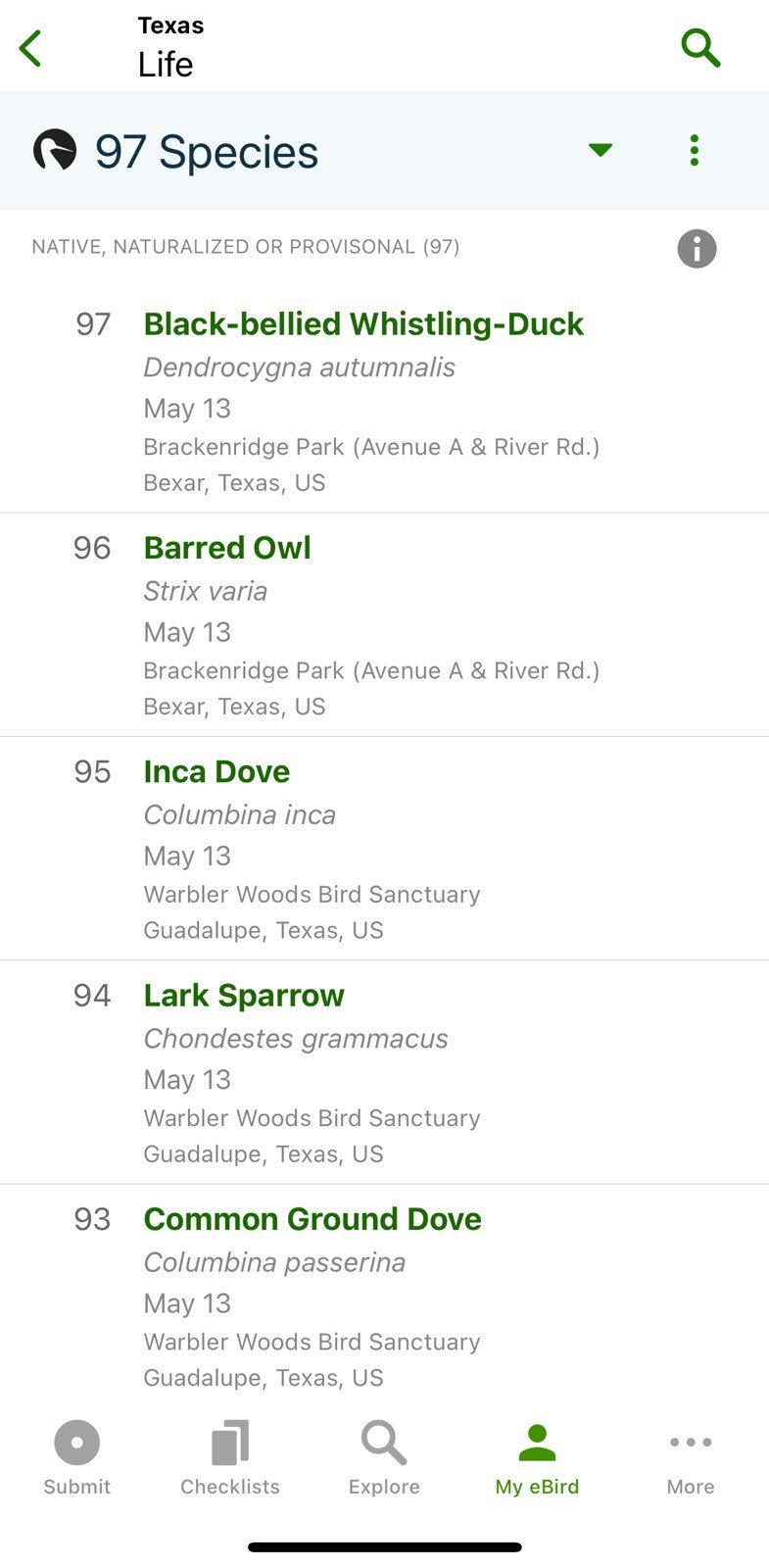

I downloaded the sister app eBird and made a free account to start tracking the birds I saw.

And now I've been tracking for five years!

Today I tell you very honestly:

Becoming a birder was one of the best things I have ever done.

It has fundamentally changed my life.

I feel happier! I’m a better listener. Outside more. Moving more. Less screens. More patience.

I feel like a better dad, husband, son … and self.

Today I'm 45.

Started birding when I was 40.

If I knew how big a difference it would make I would have started sooner!

I think for years I just needed a nudge.

So for the younger me, for anybody out there who needs a nudge, I am here today to tell you it is absolutely, definitely, a million percent time for you to become a birder.

Here are 8 reasons why:

1. It’s good for your body

Does your back hurt? Neck sore? Mine, too. Curling our bowling ball heads around tinier screens—squinting our eyes, squeezing our spines. Uhhh. Talked to a chiro or physio lately? Business is booming! Screen use has skyrocketed. And sitting. So much sitting! Been a decade since we declared “sitting is the new smoking” and yet … here we are, still sitting. Desks, planes, couches—just look around. Everyone's sitting! Well, birding shakes up our sedentary lifestyle and acts as a slow and natural physiological readjustment against these forces. Birding helps us look straight again ... and then up ... and then deep. We widen our aperture staring into forest canopies instead of squinting into tiny techy watches. And let's not forget Dr. Qing Li’s incredible research on 森林浴—aka “shinrin-yoku,” aka “forest bathing”—which shows trees release phytoncides which naturally reduce blood pressure, reduce blood sugar, reduce cortisol, reduce adrenaline, and increase production of NK (“anti-cancer”) white blood cells. Birding is good on the body.

2. It’s good for your mind

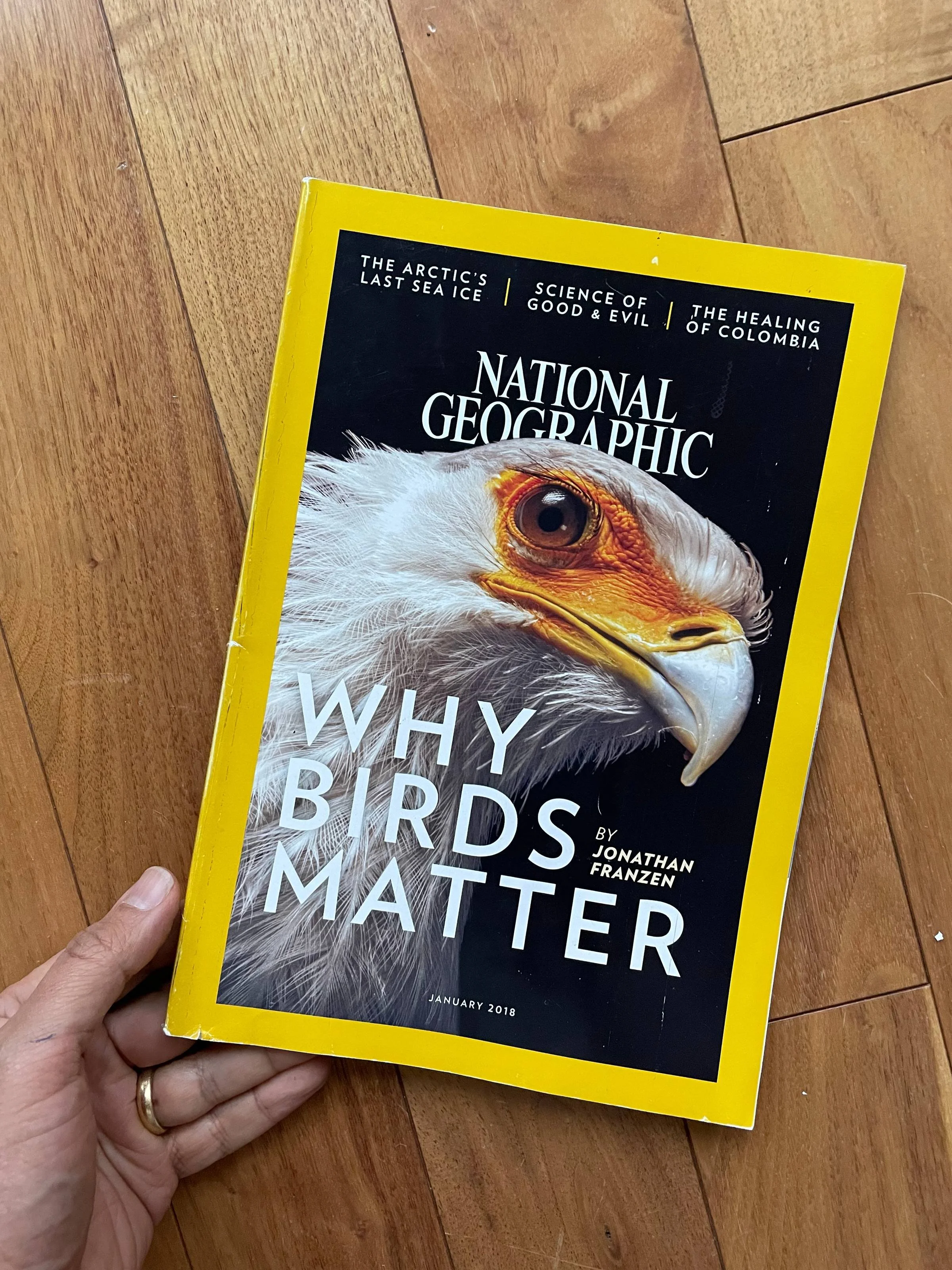

Jonathan Haidt, author of ‘The Anxious Generation’ (04/2024), has shown TikTok’s own internal strategy is to ensnare younger and younger people into its addictive forever-loops. He quotes internal documents that report using social media platforms creates “a slew of negative mental health effects like loss of analytical skills, memory formation, contextual thinking, conversational depth, empathy, and increased anxiety.” We know we have a problem! That’s why there’s a siren call globally right now to get screens out of schools. Maybe it goes back to Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986) warning us that computers may lead our brains to be “thoroughly employed in amusement ... in entertainment” or Neil Postman (1931-2003) writing in ‘Amusing Ourselves To Death’ that “People will come to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.” To our endless scrolls and fracturing focus birding offers a vital prescription. Do you remember waiting? Like … just waiting. For 10 seconds. Without grabbing your phone. Birding grows that muscle. And when you nurture it back it feels good, so mentally soothing, that you’ll soon start waiting, looking at a tree or pond or sky, for … 20 seconds? 30? And how about listening. Really listening. Not to headphones but to true three-dimensional deep, rich, luxurious listening to the earth type listening? I forgot I ever did that! Birding grows back that muscle. Hearing birds and insects and water and trees—mmmmmm. It's medicine I didn't even know I needed. Plus, I’ll add these days just the practice of looking at birds—instead of billionaires, influencers, or politicians—is activism. A way to straw-puncture the algorithmically-enhanced plasti-wrap slowly suffocating us and then frantically rip it off to stand up briefly outside the matrix. I met a photographer at the Warbler Woods Bird Sanctuary in San Antonio last year and he was calmly, serenely, sitting beside a pond … all day. He had his camera and told me the MacGillivray’s Warbler came to feed every hour or so. He struck me as some kind of enlightened Buddha. Calm, patient, tranquil. I may never get there! But birding nudges us that way.

3. It’s easier than ever

You know how John James Audubon (1785-1851) used to bird? With a gun. Birds were too far, too fast, too flitty to see in detail. And binoculars weren’t invented until after he died! So he shot them, then studied them, then painted them. His giant painted ‘plates’ served as something like a precursor to Field Guides:

But today? Skip the gun! You don’t technically need anything but it helps to grab binoculars (I recommend Nikon Monarch 8x42s), any local field guide (‘Birds of Ontario’ is my best local and Sibley's Guides are always great ... plus J. Drew Lanham reminds us used ones from thrift shops are fine!) and, of course, to download the aforementioned totally free and (generously) ad- and sponsor-free apps Merlin ID and eBird. They’re run by Cornell University (props to Cornell!) and so easy to use. The Merlin app’s newer “Sound ID” feature is often called ‘Shazam for Birds’ because you simply press a button and it immediately tells you what birds you can hear right where you’re standing! Like I was standing in Houston last month and pressed this and got this—

I will add that the SoundID is equally helpful at not-clocking those sounds you always thought were birds but maybe aren't. Toads, frogs, bats, raccoons? Been there! Many times. And SoundID is on top of the aforepictured “Bird ID”—that size-and-color feature that helped me ID the Rose-breasted Grosbeak. (Which, btw, is definitely my ‘spark bird,’ a term loosely defined as ‘the bird that gets you into birding.’) eBird also keeps helpful records of every bird you see and acts like the best social media network ever—donation-based with no ulterior motives!—to help you (for example) find the Top 100 birders in your hometown (congrats Alec—#96!) or the Top 100 birders in the world (I picture #1 Peter, #2 Steve, and #3 Jürgen as some kinda alterna-Steve Martin, Jack Black, and Owen Wilson) and then you can just click people’s names to follow, connect, or reach out to see if they're up for birding. I have met many friends this way! But more on that later.

4. It makes you less speciesist

When I was little I’d heard of sexist (discriminating based on sex) and I’d heard of racist (people yelling “Paki!” at me across the two-lane highway up north when I was visiting my cousin Manju) but I hadn’t yet heard of ageist (discriminating based on age) or ableist (discriminating on ability). And, you know, I’ve been ageist, I’ve been ableist. That’s … sort of how you learn them—through an experience that helps illuminate your own behavior. We’re blind to so much. So much! And to that end birding has helped me become less speciesist. The more time I spend with birds the more I see them as just another creature we share the planet with. We talk, sing, shiver, mate. We nest. We raise young. We hunt for food. They’re just like us. Just trying to make it work, trying to make it alllll work. And you know what? They have! We’ve been here (generously) 3 million years. Flying dinosaurs arrived 150 million years ago—but birds? If we want to go by modern definitions? 60 million. Still, that's 20 times longer than us! We were living in trees 3 million years ago. 60 million years ago we looked like tree shrews! So when we see us, our species, prioritizing our quality of life in exchange for absolutely decimating theirs? It hurts. It can’t not hurt. You see the newspaper articles with new proposed megahighways and mourn the swallows who'll need to fly deeper into the night for fewer and fewer insects over fewer and fewer ponds. Or the Bobolink or Eastern Meadowlark who are losing their grassland homes as we pave paradise to put up parking lots. (“They took all the trees and put 'em in a tree museum, And they charged the people a dollar and a half to see them.”)

Bobolink via Birdfact